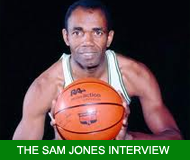

The Sam Jones Interview

By:

Michael D. McClellan

|

Thursday, October 11th,

2007

Imagine:

The greatest athletic deal-closer of the twentieth century is celebrated

endlessly, his name floating atop every all-time championship list and

dropped into every serious debate over who has exerted the greatest

influence on their sport, his close personal friendships awash in celebrity,

royalty and head-of-state chutzpah. His likeness is iconic, a symbol of

championship excellence against which all others in team sport are

measured. His legacy as the ultimate bottom line, results-oriented

exclamation point is long since secure, the label ‘winner’ perhaps more

synonymous with his name than any athlete in history. And yet when Bill

Russell – yes, that Bill Russell, the one with the signature laugh

and all of those championship rings, many of them coming at the expense of a

certain statistical glutton named Wilt Chamberlain – is asked to name the

single greatest player he has ever been associated with, the answer comes

quickly and without hesitation.

all-time championship list and

dropped into every serious debate over who has exerted the greatest

influence on their sport, his close personal friendships awash in celebrity,

royalty and head-of-state chutzpah. His likeness is iconic, a symbol of

championship excellence against which all others in team sport are

measured. His legacy as the ultimate bottom line, results-oriented

exclamation point is long since secure, the label ‘winner’ perhaps more

synonymous with his name than any athlete in history. And yet when Bill

Russell – yes, that Bill Russell, the one with the signature laugh

and all of those championship rings, many of them coming at the expense of a

certain statistical glutton named Wilt Chamberlain – is asked to name the

single greatest player he has ever been associated with, the answer comes

quickly and without hesitation.

“In the years that I played with the Celtics,” says Russell, “in terms of total basketball skills, Sam Jones was the most skillful player that I ever played with. At one point, we won a total of eight consecutive NBA championships, and six times during that run we asked Sam to take the shot that meant the season. If he didn’t hit the shot we were finished – we were going home empty-handed. He never missed.”

Imagine: You are Sam Jones, and Russell’s words waft over you from just a few feet away. You are humbled by them, and your usual loquaciousness evaporates at the sincerity of the proclamation. The loss of words is easy to understand; Russell, never one to offer undeserving praise, is beautifully matter-of-fact in his assessment of his close friend and former teammate. It is the ultimate show of respect, and you are reminded of 1969, when Jones had announced his retirement and Russell had decided to keep his own retirement plans under wraps, so as not to detract from the magnitude of Jones’ twelve seasons in a Boston Celtic uniform.

“No one compares to Bill Russell,” Jones finally responds. He is seated with six other NBA legends, some of the greatest to ever pick up a basketball – Jerry West, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Magic Johnson and Julius Erving among them. This is the Bill Russell Adult Fantasy Basketball Camp, a one-time opportunity to rub elbows with hoop royalty. “With all due respect to the gentlemen around me, Bill Russell was the smartest, most driven basketball player the game has ever seen. To this day he remains the single most influential force in team sports of any kind.”

And so it goes. Friends for life, Russell and Jones share a mutual respect forged by the blast furnace temperatures of championship basketball, one that comes from laying it on the line together, night in and night out, and ultimately walking away together, on top. For Jones, the journey began in the small town of Laurinburg, North Carolina, where sports flowed freely from one season to the next, and where baseball appeared to be his strongest suit. Not that he dreamed of becoming a professional athlete; times were different in the 1940s, and the teenaged Jones saw himself becoming a teacher. Sports represented a shot at a scholarship, a chance to experience life as a college student, an opportunity to pursue his dream career as an educator.

Determined to make athletics a means to that end, Jones played basketball well enough at Laurinburg High School to generate genuine interest from a number of prominent colleges. He attended North Carolina Central, a small black NAIA school in Durham, where he played for the legendary John McClendon, who had learned the game from Dr. James Naismith, and where Jones found himself free to push the boundaries of his emerging talent. Had Jones played today he would be considered a blue chip basketball phenom, but back then many of his sublime collegiate performances went largely unnoticed. There simply were no Internet chat rooms, no cell phones, no text messages, no 24 x 7 sports channels beaming coverage to all points on the globe. Jones’ exploits traveled slowly instead, by word-of-mouth, which is how another legendary coach, Arnold “Red” Auerbach, came to take a chance on the unknown talent from a school that was barely on the basketball map.

Selected eighth overall by Auerbach in the 1957 NBA Draft, Jones arrived in Boston wary of his chances of making a team that had just won its first championship. The Celtics boasted two All-Star guards in its starting lineup, eventual hall of fame players Bob Cousy and Bill Sharman, and there was plenty of veteran competition for the reserve spots on the bench. Jones considered himself a long shot at best. Auerbach, for his part, had never seen Jones play, and he approached the rookie with skepticism. He wondered whether Jones would have the heart to survive training camp, well-known to be the most demanding in the league, and he doubted the rookie’s mental toughness to battle his way onto the season-opening roster. All of that changed as soon as he saw Jones run the first set of drills. He was sprinting without breathing hard. He was clearly prepared, and serious about the opportunity.

"When he arrived," Auerbach recalled years later, "there were three other guys almost just like Sam who were trying to make the team. The difference was the other three just thought about shooting. After a couple of days, Sam started handing out some nice passes and blocking out so other guys could shoot. You could see that he was committed to becoming a complete player."

Forced to cut veteran and former ACC star Dick Hemric to make room for Jones, Auerbach played his rookie shooting guard sparingly during the 1957-58 season. Cousy and Sharman were at the peak of their respective games, Bill Russell and Tom Heinsohn were another year wiser, and the Celtics appeared destined to repeat as NBA champions. Jones averaged a meager 4.6 points while playing in just over 10 minutes per game, and few outside of Boston knew anything about the player destined to become one of the greatest clutch shooters of all time.

Jones’ rookie season ended in disappointment. The Celtics advanced to the NBA Finals for the second consecutive season, and were overwhelming favorites to repeat as champions. Facing the St. Louis Hawks, a severe ankle injury to Russell torpedoed any title hopes as Bob Pettit and “Easy” Ed Macauley won their first and only NBA crown.

Jones saw his playing time double the following season as Auerbach began planning for Sharman’s eventual retirement. The Celtics, now deeper with Jones playing a bigger role in the offense, steamrolled the Minneapolis Lakers 4-0 to win a second title in three years. In a season defined by balance and capped with a crown, six Celtics (Sharman, Cousy, Heinsohn, Russell, Frank Ramsey and Jones) averaged double-figure scoring.

Winning it all again the next season cemented the Celtics’ stature as a dynasty in the making. Russell was clearly the league’s defensive player nonpareil, the team’s driving force, and the primary cog in Auerbach’s title-hungry machine. It was also clear to Red that Jones was the heir apparent to Sharman, and that his young shooting guard seemed to play his best basketball with the game hanging in the balance. The addition of Satch Sanders in 1960, along with the grooming of fellow backup KC Jones as the eventual successor to Cousy, gave Boston a stronger defensive presence and furthered Auerbach’s need for perimeter scoring. Heinsohn assumed that role during the 1960-61 season, leading the Celtics with a 21.3 PPG average, as Boston won its third consecutive title. For Jones, Auerbach’s attacking, fast break offense fit like a glove. It was similar to McClendon’s system at North Carolina Central, full throttle on both side of the ball.

"Our style of play at that time started the use of smaller, fast forwards," Auerbach told Pro Sports Weekly. “It was up tempo, and because it put a smaller team on the floor we had to go to the press more often. See, Sam understood his role in this perfectly. He would race the length of the court on the wing, and on defense he knew how to pressure his man. Sam was a smart basketball player.”

The 1960-61 season marked the last for Sharman, whose body was beginning to break down from the rigors of professional basketball, and it was also noteworthy in that Jones made his breakthrough into the starting lineup.